New Practical Attacks on 64-bit Block Ciphers (3DES, Blowfish)

A pair of researchers from INRIA have identified a new technique called Sweet32. This attack exploits known blockcipher vulnerabilities (collision/birthday attacks) against 64-bit block ciphers like 3DES and Blowfish. It affects any protocol making use of these “light” blockciphers along with CBC-mode for a long period of time without re-keying. While cryptographers have long known that combining block ciphers with long lasting connections have these security implications, but it is relatively easy for product maintainers or users of various software to create vulnerable conditions.

In the case of TLS, the attack can be performed actively instead of passively observing large amounts of communication. Attackers can utilize the same kinds of JavaScript based techniques used in BEAST to exploit Sweet32.

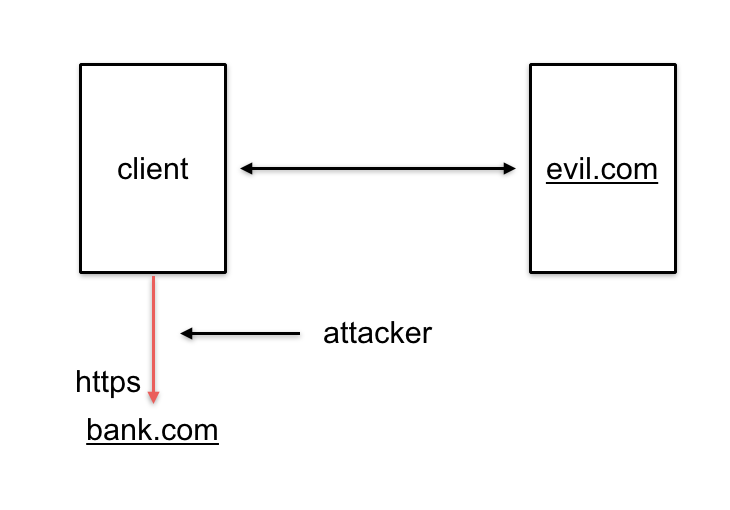

The first technique used in BEAST (diagrammed above) is to make the victim visit a malicious website which will execute some JavaScript in the victim’s browser. The script then sends many HTTPS queries to the targeted website. Meanwhile, the attacker will adopt a man-in-the-middle position to observe, or even tamper, with the connections being made by the script.

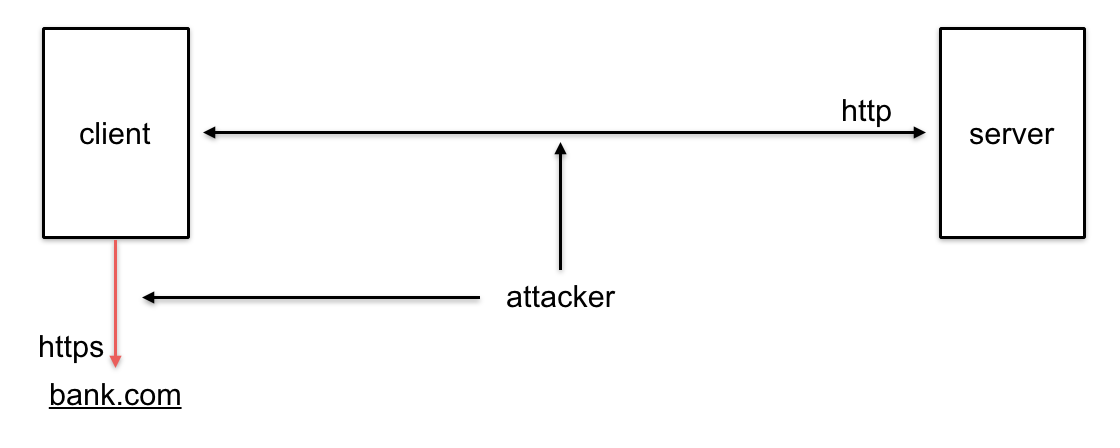

A second, and more efficient, way of doing this is for the attacker to man-in-the-middle every connection made by the victim and wait for the victim to visit an HTTP server not using SSL/TLS, as shown above. After that, the attacker can easily tamper with the responses of the HTTP server to inject snippets of JavaScript. The attack then unfolds in the same way it did in the previous BEAST-style technique.

For the Sweet32 attack to work, the server needs to support 3DES or Blowfish. The victim’s browser also needs to be old enough to request these ciphers in priority as well. By observing many messages (785 GB worth), the attacker will be able to detect a collision in CBC-mode and will be able to extract the secret (in their experiment, a 16-byte session cookie). This took on average 38 hours in the researchers’ setting, which can be deemed impractical since web servers also have the ability to limit long-lived TLS connections. It is important to note that browsers do not have this capability.

This attack was also tested on OpenVPN where it was way more devastating: for the same amount of data needed to extract an authorization token, the attack took 19 hours.

Mitigating these problems appears to be more complex than just deprecating 64-bit ciphers (which TLS 1.3 already does). Lightweight ciphers are making their ways into embedded devices, remarkably helped by NIST who has been pushing for a first draft.

In the context of TLS, re-negotiating a new set of keys (re-keying) stops the attack. But it needs to be done faster than previously thought! While most standards recommend to re-key around the birthday bound (\(2^{32}\)), this new research shows that it is insufficient. The probability of detecting a collision before the re-keying happens is still too high to consider it a safe countermeasure. The optimal strategy outlined in the paper is to re-key after \(2^{21}\) encrypted messages.